Greetings!

Hope everyone had a great holiday! We wish you all the best for the new year.

Another big storm is brewing in the Sierra and the skiing and backcountry conditions are getting even better! Mimi, Craig Dostie and I are going out for a XCD backcountry tour tomorrow from Donner Pass, old Hwy 40 (the old ASI Lodge) to Donner Summit, Hwy 80. It's a great tour with outstanding views and wonderful rolling terrain.

We are passing along a new article that is just out in a great publication, the Adventure Sports Journal. It has a lot about the "good old days" and where things have progressed to. Hope you enjoy it. We look forward to skiing and climbing with you soon.

Bela Vadasz: 30 Years of Alpine Guiding

From Cowboy Guide to the Peak of His Profession, This Nor Cal Alpinist Has Led the Way

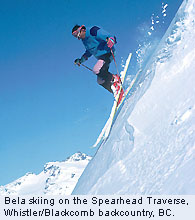

By Pete Gauvin • Photos courtesy of Bela and Mimi Vadasz

Economics and Proposition 13.

These are two of the less obvious reasons why Bela G. Vadasz is a mountain guide and owner of Alpine Skills International, the Truckee-based ski mountaineering, climbing and avalanche education outfit he founded with his wife Mimi in 1979 - making it one of the oldest and most respected programs in the country for teaching human-powered mountain travel.

Were it not for penny-pinching economics, the Hungarian-born San Francisco-raised Vadasz might not have been introduced to ski touring in the Sierra by his father when he was only six, using a pair of Sears work boots his dad rigged to fit the bindings.

"My father figured out a way that we could unhook the back hook of the cable bindings of our, at the time, wooden alpine skis with screw-on metal edges," says Bela, now 54. "That basically meant that a weekend consisted of one day of touring and one day of paying to ride the lifts....

"Part of the economics at the time, at Sugar Bowl you had to pay 75 cents more to ride the Magic Carpet Gondola (from the parking area to the base). So we would ski tour across. Then we'd hook the heels down for the rest of the day and ride the lifts."

Ironically, perhaps prophetically, the very first skiing Bela ever did was right outside what would decades later become the ASI Lodge, at the top of Donner Summit on Old Highway 40.

But what does Bela owe to Proposition 13, the property tax initiative California voters passed in 1978? Well, without it, the impetus for starting ASI might never have come about... But let's back up a bit first to get the full picture.

Cutting His Teeth in the Sierra

An only child, Bela's formative childhood years were spent exploring the Sierra with his father, Bela, and mother, Eva.

"My family immigrated when I was three and I grew up in San Francisco and I had a really good opportunity with my parents to visit the Sierra - a lot.... In 1959, I pretty much started skiing and backpacking and peak bagging with my parents, and so I just got that deep-rooted love for the Sierra."

Around this time, the backpacking boom of the '60s was getting underway. A young Bela was able to tag along on harder core trips with his dad's Austrian friends, who shared a lot of their mountain savvy with him. "They inspired me tremendously," he recalls.

Common destinations included the Tuolumne Meadows high country, Cathedral Peak and Mt. Lyell in Yosemite.

"We'd do like an 11-day trip from Tioga Pass to Devil's Postpile by Mammoth," Bela remembers. "When I got a little older, about 10, we'd do a lot of peak ascents along the way - Class 2 (off-trail scrambling), Class 3 peaks (hand/foot holds needed), until we had to turn back... We didn't know how to use a rope, didn't have a rope."

That was an impediment Bela was destined to overcome.

The Summer of '69

At 16, Bela went to Europe with his father. It was the summer of 1969 and they spent quite a bit of time in the Alps.

"I got to see what mountain guiding was all about. Watching guides bring their clients back to the hut after a spectacular day and seeing the camaraderie and spirit of all that. That's when I said, 'OK, this is something I'd really like to pursue.'"

One of the peaks they climbed was the Grossglokner, the highest peak in the Austrian Alps. Years later it would take on a special significance.

Back from Europe, Bela went straight to Yosemite Valley. "That's when I just went haywire there with Class 5 skills (more difficult rope and belayed climbing)."

Over the next couple years, Bela became active in the Berkeley-based Yosemite climbing community, first with the Sierra Club Rock Climbing Section (RCS) and later with the American Alpine Club.

"At that time, the best climbers were Sierra Club members and they were terrific mentors. People like Allen Steck and Jules Eichorn. These Sierra legends were the people leading most of those weekend trips and so it was an opportunity to pick up a lot as a youngster."

Pulled in by Scuffed Boots

Bela enrolled at San Francisco State University to study outdoor recreation. That's when he met Mimi Maki, a Finnish and French girl who grew up in the East Bay.

"I noticed toe scuffs on her hiking boots and I knew there was only one way those toe scuffs got there. That's from some serious off-trail climbing where there's a lot of contact with the rock."

From love at first scuff, the two spent a lot of time "climbing and skiing anything we could."

Learning the Ropes as Guides

While doing undergraduate and grad work in Recreation and Outdoor Education, they became leaders in the university's outdoor club and then began leading trips for several continuing education programs in the Bay Area, including Marin Adventures through the College of Marin and Outdoors Unlimited through the University of San Francisco.

In the early '70s, university outdoor programs were still in their infancy. "There was a traditional-based curriculum going on (at San Francisco State)... We started to develop more contemporary outdoor programming with cross-country skiing, backcountry skiing, rock climbing and mountaineering."

This is where they learned how to teach and develop a curriculum that combined elements of the traditional European alpine guiding model and new developments in experiential education.

"We just borrowed from the best of both and fused them into a process and a concept," says Bela. "That was the basis of our program which still to this day has a lot of educational ideals attached to it, not just pure guiding."

Much of their teaching style was derived from ski instruction and training with the Professional Ski Instructors of America (PSIA). "Hooking into PSIA early on helped teach us how to teach. We could apply it to pretty much any outdoor skill in terms of how to design a teaching progression."

Meanwhile, Bela and Mimi were also being mentored by two of the leading alpinists of the '60s and '70s, Chris Jones and George Lowe, through the American Alpine Club. Actually it was sort of a quid pro quo relationship: Jones and Lowe imparted knowledge from their numerous first ascents in the Canadian Rockies, while Bela and Mimi schooled them in skiing on marathon ski traverses across the Sierra.

"They taught us a lot about going fast and light in the mountains, but we had the skiing thing going and they were really intrigued by that and so it allowed for a little bit of an exchange," says Bela.

Switching Revenue Streams

Guiding for college programs seemed like a good gig until the "People's Initiative to Limit Property Taxation," a.k.a. Prop. 13, arrived on the door step in 1978, threatening to severely crimp public education funding.

"That was a big scare for us. We feared that all these continuing education programs would get cut," Bela says. "That was the impetus to move into the private sector and start our company in 1979."

While the fallout from Prop. 13 has had a myriad of debatable benefits and drawbacks, one of the unpublicized perks, for thousands of aspiring skiers and climbers to follow, was the creation of Alpine Skills International.

Ski Touring Set Them Apart

While ASI was about all aspects of alpine travel, there were already other climbing schools and programs operating, such as the Yosemite Mountaineering School. Bela and Mimi felt their young company needed something to distinguish it. They found it in backcountry skiing.

"Skiing kind of challenged us because there was no one else doing it," says Bela. "It was such a new frontier at the time. A lot more people had climbed El Cap than had crossed the Sierra on skis."

The gear of the day only added to the challenge.

"We had these terrible skinny skis and floppy boots and we just did the best we could because that's all we really had. It was either that or really heavy gear that was slower in the long run for us."

Their secret for success in the Sierra was timing.

"We sort of found that magic window from the middle of April to the end of May, six weeks when the snow would corn up in the high country. And that's why skinny skis worked because we could stay on top of the snow."

For many avid backpackers and climbers, ASI's guided ski trips opened the door to seeing the "Range of Light" in an entirely new dress.

"We could get around and be mobile and we could see the incredible mountain range of the Sierra Nevada where granite was now accented with all the snow.... In a way, I think that was the real beginning of the good stuff."

Going Back to the Alps

The next stage in ASI's evolution was the addition of trips to Europe.

"When Mimi and I had a chance to go back to Europe in the summer for alpine climbing, just the sight of the awesome grandeur blew our polypropylene socks off. Then to go back there and ski, that was another fantastic experience."

Bela has done the Haute Route from Chamonix to Zermatt 21 times since 1983. "That's where I really learned to ski guide. I was able to work directly with European ski guides."

But guiding American clients on the Haute Route presented additional challenges that had nothing to do with language.

"People would read about Haute Route in magazines and say I want to do that. But in Europe people are more experienced ski tourers. To bring greenies over there from the Sierra, that was big country with some serious challenges. We learned the hard way that we had to prep people up a little more to help get them ready."

Tweaking the Guide Model

While there was much to be learned from the Euro guides' practices, the European guiding model - small ratio 1:1 or 2:1 high-cost guiding -- was not something that would fly here, Bela says.

The American model of larger groups made it more affordable for more people to participate. It focused more on education than personalized guiding, in part because the Sierra's more benign terrain and weather makes going without a guide more of an option.

"The influence we got from going back to Europe and tracing the roots and the history and understanding the tradition and the need for the style of guiding based on those alpine peaks, their size and their magnitude and the length of the routes was invaluable. (That terrain) dictates a whole guiding style that's necessary. California's mountains are a little more forgiving. You could take a do-it-yourself mentality and could get a way with it, sometimes."

It's more than just size that determines a different guiding approach.

"In a way the hardcore Alps are more accessible. You can take lifts and do a pretty hard route and be back down that day. Whereas in the Sierra it usually takes a day just to get up there.... It's more of a mountain experience there, where here it's more of a wilderness experience."

Rounding Up Cowboy Guides

These differences and the lack of a standardized, unified credential system contributed to the perception that American guides were, as a whole, a notch below their European peers.

"Here in America we were cowboy guides. There was no doubt about it. And it worked for the time and the era and organic period that was going on in the late '70s. But it didn't cut it in the big mountains and it took us a while to adjust and adapt."

Bela played a key role in trying to change that.

The first big step was the inception of the American Mountain Guides Association in the early '80s. The AMGA created a rigorous certification and examination process for guides in three disciplines: Rock, Alpine, and Ski Mountaineering. Bela, who is certified in all three, directs the Ski Mountaineering program.

But gaining the peak of international recognition was still far from view, and many AMGA guides were not convinced it was a worthwhile endeavor. Bela was not among them. Beginning in the early '90s, in his role as coordinator of the AMGA's Ski Mountaineering program, he helped spearhead the campaign for acceptance into the International Federation of Mountain Guide Associations (IFMGA).

"It was a big learning curve. Not everyone had been to Europe and seen the IFMGA... It took almost 10 years before the AMGA was ready to be accepted by the IFMGA."

Coming Full Circle

That day came in 1997 at the IFMGA's annual meeting, which rotated locations from year to year. In 1997 it was held in Austria, in the village right underneath the Grossglokner, the very same peak Bela had climbed with his father nearly 30 years before.

Bela and one other American guide, Mark Houston, were there to receive their IFMGA pins, signifying the highest recognized certification in mountain guiding in the world.

"(The experience) was absolute full circle," says Bela. "That IFMGA acceptance was a huge step, a milestone in recognizing the professionalism of mountain guiding in America."

To qualify as an IFMGA guide, you have to be certified by the AMGA in all three disciplines, a rigorous training and certification process that usually takes three to five years. That's why Mimi, a certified AMGA ski mountaineering guide, did not pursue IFMGA certification as well: They couldn't both afford the time commitment while raising their two boys.

Today, there are just over 50 American guides who have gone through the entire process. By comparison, in Switzerland alone, one of the core alpine countries where the federation started, there are more than 1500 IFMGA guides.

While the role of international recognition in American mountain guiding is young and developing, "each year the value of that certification process becomes more apparent."

Mountain Guides not Horse Packers

With IFMGA certification now established, Bela has been working to extract a constant thorn in the side of guides for years: land access and the convoluted, restrictive permitting process.

"In Europe when you have your IFMGA certification you can go anywhere... Here, we face a big challenge with land managers to obtain little bits of turf we can guide on."

The U.S. Forest Service and national parks, for instance, issue outfitter guide permits based on a "horse-packing model" and "we're lumped in that same category," he says.

"I'm fortunate because I got a lot of permits early on before they put moratoriums on them. A lot of young guides right now in America want to get their IFMGA pin just so they can go to the Alps and guide. We still face that huge challenge here of the land managers not really having the courage to say, `OK, you're a certified guide, you can guide. If you're not a certified guide, you can't guide.'"

Bela believes guides who began guiding before certification should be able to keep guiding and finish their careers. "But in this day and age, certification is here, it is in place and everyone should embrace it. The public should, the guides should and the land managers. But those kind of things take a lot of time."

Remembering the Lodge

Before the drive to gain international certification started, there was another more visible outgrowth inspired by Bela and Mimi's trips to the Alps: the ASI Lodge at the top of Donner Summit.

A basic Euro-style bunk and breakfast, the lodge provided inexpensive shelter ($24 for bunk and hearty breakfast), a meeting place for adventurous souls to hook up for trips, and a place for ASI to stage its courses and present slideshows of grand adventures. It opened in 1983.

"Back then it was at the end of the plowed road so you really had a feeling of isolation there. It was almost like you were taking your first step into the backcountry," says Bela. "It was great for ASI because it was a feeder that got everybody excited."

The lodge ran for 18 years before Bela and Mimi closed it in 2001 and it became home to the Sugar Bowl Academy.

"Times changed and it became more of a place for people looking for a cheap place to stay, which eroded its purpose. Between running the lodge and the ASI program it took every bit of our time, and we needed to focus more on our boys (Tobin, now 16, and Logan, 12)... The other benefit is that it allowed us to refocus on ASI programs and develop them to what we have now."

Adjusting to a New Market

Today, operating out of the upstairs of The BackCountry store in Truckee, ASI still works with all levels of the public but a big chunk is now focused on guide training. Bela's biggest client is the Marine Corps Mountain Warfare Training Center on the east side of Sonora Pass. Bela trains about 50 Marines per year to be instructors in each discipline: ski, avalanche, rock climbing and alpine mountaineering.

Significant changes have been made to ASI programs for the public, too. Today there is a much greater emphasis on avalanche education and less demand for ski training.

When ASI started, almost everything they taught was the next step beyond backpacking.

"Today, there isn't that common thread to build on. For example in climbing. Climbing was an extension of backpacking. People came as backpackers that couldn't get to the top of the peak.... Nowadays they come from the climbing gym. So they don't really have that deep-rooted feeling of love for the mountains already in place."

Backcountry skiing was an extension of backpacking, as well. "But now, just like rock climbing comes from the gym, it's skiers coming from the resort. People hone their skills at the resort and catch wind of the idea of going out of bounds: A little side country at first, then a little backcountry, then developing their skills to go deeper into the backcountry."

Avalanche education was less of a concern when skiers waited for the spring corn season to explore and the gear limited the number of skiers who would challenge avy-prone terrain.

"Back then it took us years to build our skills and confidence on that skinny, crummy gear. And in the process, we did learn a little bit more about the mountains and avalanches. Now people in their first year are getting right into the terrain in the dead of winter... People accepted a slower learning curve back then. Now they want the goods right away."

The growth of snowboarding and improvements in Alpine Touring gear have also made it significantly easier for thousands more people to get into the backcountry without having to undergo a long apprenticeship in telemark skiing.

"Backcountry skiing is having a big boom and the avalanche education is an integral part of the whole thing. But there's really no shortcut to learning all these skills. It's over time that you develop the intuitive senses and the observation skills and the knowledge."

Recognizing this, Bela is working to put together an AMGA course for top-level ski instructors (PSIA Level III) so that they can guide out of bounds at ski areas and introduce people to off-piste backcountry conditions with an experienced, certified guide.

It's all part of the continuing evolution of guiding and ASI, which today continues to thrive by adapting to the environment. Just like a guide would.

|